My Country Wept…

Theo did as he was told and laid his head down on the floor, waiting for a machete to end his life…

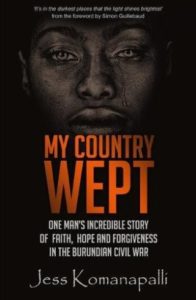

Here’s a massive recommendation to buy yourself (and for others too) this newly-published book about my friend Theodore Mbazumutima’s truly extraordinary story. He should be dead, but somehow, on multiple occasions, his life was spared.

So please order your copies here for the UK and here for the USA.

Enjoy! (although I’m not sure that’s the right word)

This is a story of soaring hope in the most hideous of circumstances. Yes, there are good news stories to be told from Burundi!

THAT’S THE END OF THE BLOG, FEEL FREE TO STOP THERE. I actually told some of Theo’s story in my book Dangerously Alive, so if you want to read more (it’s quite long), here goes:

At the end of 1993, tens of thousands of Burundians were being murdered on both sides of the tribal divide as genocide kicked in following the assassination of the Hutu President. As a Hutu, Theo had to flee, or otherwise he would have been killed by the Tutsi. He walked several hundred miles through the bush into Tanzania. On the way he had a number of extraordinary escapes.

At one stage he was taken by a blood-crazed gang of Hutus, who insisted that he and his five friends kill some Tutsis to prove they were Hutus. Theo was the leader of the Christian Union at school and the other five looked to him. The choice was basically to kill or be killed. He chose to be killed. He was forced to lie down on the floor, where he prayed a feeble prayer of resignation and waited for the machete to land on his neck. But suddenly a military helicopter flew overhead and everyone dispersed in different directions, so Theo and his friends continued their journey.

Further on, as they crossed a tarmac road, a military tank spotted them and sprayed them with bullets. As they fled, many were mown down, but again Theo survived and continued making his way through the bush. Later he and his group found themselves surrounded by a Tutsi mob. Their end had surely come. There was no escape. But suddenly a Tutsi girl he had once helped with a work assignment at school years before ran up to him and jumped in his arms. “If you want to kill him, you’ll have to kill me first!” she cried. Her brother was influential in the army, so the murderers let him go.

Once in Tanzania, thousands of Hutu refugees were dying of dysentery. Theo lay down to die, questioning why God would have spared him so much only for him to die now, without even having had the opportunity to testify to God’s glory. Suddenly a white man drove up in a truck, lugged him and a few others into the back, and took them to a hospital. One of them died on the way. Theo was given medicine before being dumped back in the bush. That was enough to save him. Some time later, a female Swiss doctor found him and gave him a job, training him up as a nurse.

As the refugee camps became more established, all young men were being forced to join the rebel Hutu movement, but Theo didn’t want to, so he fled to Kenya with some others. He was caught by the Kenyan authorities and was going to be deported when a mystery woman (most likely a prostitute from her manner) for whatever reason came to their aid, going to the immigration officer who was about to sentence them to deportation and imprisonment, and arranging for him to release them. They were whisked off to the officer’s house, given clothes, food, a chance to wash, and false Tanzanian papers enabling them to get into Kenya and apply for asylum.

Theo’s remarkable journey continued as a missionary he hardly knew sent off an email on his behalf and Theo was able to go to Bible college, first in Kenya, and then at Allnations (where we met) in England.

That concise summary doesn’t do justice to Theo’s whole story, but during the time I spent with him, he raised some issues from his experiences which profoundly challenged me:

1. He said that God’s faithfulness does not depend on man’s faithfulness. As he lay there waiting to have his head chopped off, he said his prayer was utterly faithless. But God in His grace had mercy.

2. He had a wholly inadequate grasp of what constitutes salvation. He’d been taught that you come to Jesus to be saved from hellfire and to get a ticket to Heaven. But he wasn’t equipped to live on earth. We don’t just believe in life after death, but life to the full before death, and a fuller understanding of salvation equips us to engage on both levels more effectively.

3. There was the time when he was languishing in the Tanzanian refugee camp. He was angry at everyone – the other tribe for killing his tribesmen, the international community for not helping them fast enough, the manipulation of politicians etc. People were dying all around him and his greatest anger was directed at the Church. “Where is the Church?” he asked himself. Islam spread fast in the refugee camps because Muslims were there providing emergency relief and sharing their things, whilst the Tanzanian churches stayed away. Many converted to Islam purely because they said, “The Muslims are the ones who love us.” However, as his anger boiled over at God, he heard the Lord reply, “YOU are the Church!” And with that understanding, he got his hands dirty, mucked in, and shone as a beacon of light in the darkness.

4. He said, “Don’t ever underestimate small acts of kindness” – the bits of food people gave him, the medicine, the mystery prostitute or white man in the truck, the email sent to a faraway Bible college. Sometimes looking at Africa the problems can seem so overwhelming that we resist getting involved, but his story included lots of crucial little acts of kindness and intervention that kept him alive and led to him now being able to fulfill God’s destiny and make a big impact on his nation.

5. His legitimate and deep-seated prejudice against Tutsi was profoundly rocked by that young lady risking her life to save his. She was prepared to die for him. No longer could he lump all Tutsis together as evil people. There were good and bad amongst both Hutu and Tutsi.

I am humbled by his story on many levels and it makes me want to learn these key life lessons:

1. Thank God that His faithfulness doesn’t depend on mine! I will choose to live a life oozing grace and gratitude for His intervention in my ongoing journey.

2. A full view of salvation includes life both before and after death. Is my own view defective or imbalanced? The stakes are high so I want to give my all to seeing people saved for eternity, but also so that they fully engage in this life too.

3. When I’m tempted to get angry, despairing or frustrated about the Church, when I next criticize or disparage Her, may I stop seeing the problem as being “out there” and instead hear God’s rallying cry: “YOU are the Church!”

4. What small acts of kindness can I do today which, under God’s sovereign hand, could lead to beautiful fruit in the future?

5. For me, my prejudices aren’t so much towards Hutu or Tutsi, but I most certainly have them. We all do. And as followers of Jesus: an immigrant, a refugee, an outsider, we Christians have ironically had a very mixed track record in this area. So what is my attitude and how am I actively engaged in helping the foreigner, the outsider, the immigrant, the alien, the marginalized? Or is following Jesus about being a cosseted member in the safety of the in-crowd?

It’s worth thinking about…

4 Comments

powerful story and life, Simon. Our God is amazing and so faithful. How can we ever doubt. Thank you for sharing the lessons learned. The one I like best is God speaking to the disgruntled believer – “You are the Church”!

Mary Lou

Thank you Simon for sharing! Your have summarized very well my story. To God be the glory.

Theo

Thank YOU Theo for such a story! Though I live in the ‘rich west’, the rich west is broken and I too am broken, in body and in every other way, and we all share life together on God’s poor, broken, once-beautiful but still marvellously-loved world which our loving Father refuses, EVER to give up on! Nor can we ever imagine what this unfathomable love has cost him!

Sorry about the preaching, I just had to say that for myself!

Ann

Huuum! Good to read this story. Even thaugh I know Theo, I didn’t know this (his) story.

Thank you Simon.